Coppi and Bartali in the 1949 Tour de France

Last year we reviewed two books about Italian campionissimo Fausto Coppi. I have to confess to being a bit of a Coppiani, ever since seeing a picture of Coppi (“perfection on two wheels”) in action. Most articles about Coppi also talk about his great rival Gino Bartali. Many dismiss him as “Gino the Pious” or “Ginettaccio” (Gino the terrible) due to his testy temperament. But there is a lot more to Bartali than this, as the first English account of his life reveals.

Road to Valour starts in the early years – Bartali got his first bike at 13, and quickly started winning races. He wasn’t a smooth rider like Coppi, preferring instead to wear his rivals down with repeated attacks. But his work ethic and determination to win were very strong, driven partly in response to getting bullied at school. He turned pro at 20 and won his first Giro in 1936, aged just 21. His first Tour victory followed in 1938.

By this time, Europe was sliding towards war, and Mussolini’s Facist government wanted to hold up sporting successes as evidence of Italian racial superiority. This was a political minefield for an athlete. Bartali, already a devout Catholic, took a big risk by choosing to align himself with the Catholic Church, rather than dedicate his win to Mussolini.

There was little racing during the war years, and Bartali effectively “lost” the best years of his cycling career. As Mussolini’s popularity faded, the Nazis stepped in to support him, and with that came increased persecution of foreigners, and in particular Jews. Bartali was still allowed to train, and this freedom led Cardinal Elia Dalla Costa to ask him if he would deliver forged identity papers to help those at risk. This work was dangerous, and very secret at the time. It was only decades later that some sketchy details emerged. Bartali himself never spoke openly about his role, but it is estimated that he saved many hundreds of lives.

Bartali experimented with an early form of deraillieur gears

Racing started to pick up again in 1946. Although Bartali won the Giro in 1946, he was now in his 30s and often struggled against younger opponents. He adapted his racing style, and by 1948 he was picked to lead the Italian national team in the Tour. However, after 2 weeks of racing he was 21 minutes down at the rest day in Cannes and all hope of a second Tour win seem to have gone.

Back home in Italy, the leader of the main government Opposition Party was shot, and it looked like the country was going to spiral downwards into civil war. That evening the leader of the ruling Christian Democratic Party phoned Bartali and asked for help. If Bartali could win the next day’s stage, perhaps his victory would help to reunite Italy.

Bartali and French rival Bobet fight through atrocious conditions in the Alps

The stage was 167 miles, over three massive Alpine climbs. Many of the roads were gravel and mud. Gino woke at 4am for the early stage start to the sound of rain lashing against his hotel window. His team mate reported that Bartali laughed!

Could Bartali win the stage? And a second Tour, 10 years after his first?

And could he save Italy?

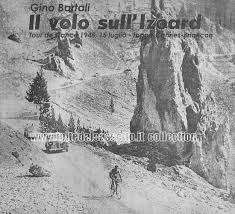

Tour legend says that the rider who enters Cassa Deserte (an area of strange rock formations near the summit of Col D’Izoard) first will win the Tour

Aili and Andres McConnon spent 10 years researching Road to Valour. It is a fascinating account of an incredible athlete, and how he faced up to challenges both within and beyond sport.

Coppi may have led cycling into the modern era with his glamour and modern scientific training methods. Bartali was the last of the old school hard men, but there is still much to admire here. I would thoroughly recommend this book. There is now some Bartaliani in me, along side the Coppiani.

Foot note – following the excitement of the Giro’s visit to Ireland last year, the first Gran Fondo Giro d’Italia is coming to Northern Ireland on 21st June this year. Registration for what promises to be an amazing event has just opened – click here for more details.